In a bio-technology lab at Harvard University’s medical school an international group of highly skilled scientists are dreaming up new ways to engineer artificial human tissue with 3-D printers. Some of their brainpower these days, though, isn’t focused on the science but instead on U.S. president Donald Trump’s immigration ban and what it means to them and to their work.

“Half of the discussions in the lab these days are about this topic and not about science,” said Saghi Saghazadeh, a 30-year-old Iranian who has been living and studying in Boston for two years, on a single-entry J1 visa.

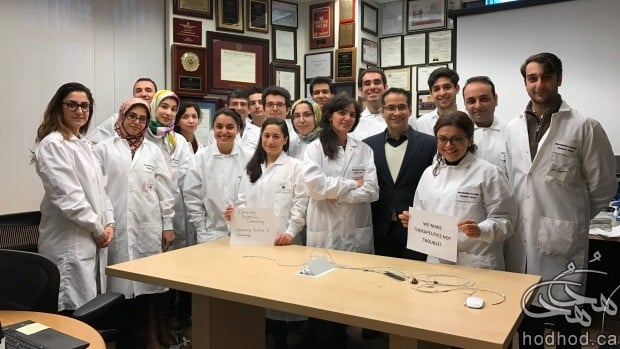

She’s one of 20 Iranians, with varying passports and visas, working in this one lab of 100 people at Harvard. It draws doctoral students and instructors from all over the world.

But their expertise doesn’t exempt them from the travel ban enacted more than a week ago.

Iran is top of the U.S. State Department’s list of state sponsors of terror and one of the seven countries whose citizens the U.S. has put under a 90-day immigration freeze in the name of — as the executive order is titled — “Protecting the Nation from Foreign Terrorist Entry Into the United States.”

Saghi Saghazadeh says she’s torn between continuing work in an exciting field and being closer to family in a country where she feels safe. (Elmira Jalilian)

Choosing between education or feeling safe

Saghazadeh, who was top of her class in Polymer Engineering at Tehran Polytechnic and won several scholarships to study in France and Belgium and eventually at Harvard, wonders if the U.S. is still the place for her.

“Do I want to be at a kick-ass scientific place but not feel welcome in the country, or do I want to be with family and feel safe? That’s the question I am asking myself,” she said.

Her parents in Iran are unable to visit her under the ban and she is unable to visit them — for now. And her dream of eventually applying for a green card is on hold. She’s reconsidering.

Of the 100 people who work in the bio-technology lab, 20 are of Iranian heritage. (Dr. Shrike Zhang)

Though the ban is temporary — she’s not convinced things will improve for people from the countries on the list. And even with a Seattle judge overturning the ban late Friday, the White House has vowed to fight back.

“I am considering going somewhere else. At some point, we want to feel welcome at the place where we are living and working,” she said.

Saghazadeh, who is working on smart bandages in the lab (these are bandages which sense things and then deliver therapies) said she’s thinking about Europe, Canada and Australia, even though she recognizes that “the best scientists in the world, in my field, are here,” she said, referring to Harvard.

Cutting off international expertise

“It is sad for science. A lot of professors who are advanced in their fields are internationals. They are all here trying to get new things done and there is a strength from the diversity of all these scientists. We will probably lose that and that is sad.”

Iranians value science and many go on to excel in their fields, which explains their presence in the Harvard lab.

Ali Tamayol, a 34-year-old Iranian-Canadian who’s an instructor at Harvard, was told by his lawyer that it was probably best not to travel in the 90-day freeze period. (LinkedIn)

For Canadian-Iranian instructor Ali Tamayol, 34, it’s all bad news. He’s also on a J1 visa, which means he had questions about whether he could travel for work or even get together with old friends from Toronto on a Mexican holiday this winter.

His lawyer told him it was probably best not to travel during the 90-day freeze period. Harvard representatives suggested the same, he said.

Harvard is trying to support its students and faculty affected by the ban. Both the president of the university and the dean of the medical school issued strong statements against the ban and the university joined seven other higher education institutions, on Friday, in filing a brief to support efforts to challenge Trump’s executive order.

“It is essential that our commitments to national security not unduly stifle the free flow of ideas and people that are critical to progress in a democratic society,” the brief reads.

‘It’s going to create a lot of chaos’

Tamayol says he was “shocked” at hearing of the executive order.

“It’s going to create a lot of chaos. The nature of the work we do requires a lot of travel to share findings and learn from each other. It is cutting us off from the rest of the world,” he said.

Lab director Ali Khademhosseini is a world renowned scientist who has a U.S. passport and Canadian citizenship, so he believes his own travel may not be affected. But he worries about the disruption for all the Iranians in his lab, plus the 25 foreigners from various countries who are in the pipeline to come to work here. Some of them have already bought tickets to fly to Boston, but it’s unclear if they have had their visas revoked or not.

Khademhosseini says he’s added his name to the thousands of American professors and scientists who oppose the ban. He protested in Boston’s Copley Square and plans to attend the Science March on Washington on April 22. (Ali Khademhosseini)

“I totally understand the perspective of needing to ensure the security of Americans,” said Khademhosseini. “I just don’t think this is the way to do it. None of the countries [on the list] have been the culprits of the terror attacks in the U.S.”

So he’s added his name among the thousands of American professors and scientists who oppose the ban. He protested in Boston’s Copley Square and plans to attend the Science March on Washington on April 22.

Immigrants important to science

“Making people realize the importance of immigrants in the science and innovation engine of the U.S. is very important,” he said.

“We’ve had Iranian-Americans who were major inventors of laser-eye surgery or have been major players in the development of companies like Google, DropBox and Oracle.”

Khademhosseini speculates about whether it will be a boon for Canada.

Americans and other expatriates gather to protest against U.S. President Donald Trump’s recent travel ban to the U.S., outside of the U.S. Embassy in Tokyo on Tuesday. (Eugene Hoshiko/Associated Press)

“There are those who are writing to me to ask about coming to Canada for post docs,” said Milica Radisic, the head of the Laboratory for Functional Tissue Engineering at the medical school at the University of Toronto, who has studied with Khademhossieni in the U.S.

The number of people contacting her is low, for now. But she knows an Iranian scientist who moved to Canada just before the ban kicked in because he predicted something like it was coming down the pipe.

If the changes to the visas and travel ban continue, they will have “long-term consequences for science,” she said.

She noted there could be less exchange of ideas, as the U.S. hosts a lot of major bio-tech and medical conferences.

“If you cut off one third of the people from being able to attend, it’s a problem,” she said.

Science doesn’t have a nationality

Already at least one University of Toronto PhD student, also an Iranian, Ehsan Alimohammadin, was detained on his way to a conference in San Francisco, a week ago Friday night . He was held for 14 hours before being flown back to Toronto.

“It’s very bad for the scientific community,” Alimohammadin told the U of T News. “Science doesn’t have a nationality or a religion. The scientific community shouldn’t be affected by a decision like this.”

An Iranian PhD student at U of T was detained on his way to a conference in San Francisco and held for 14 hours before being flown back to Toronto. Ehsan Alimohammadin says Trump’s travel ban is ‘very bad for the scientific community.’ (Katherine Holland/CBC)

The university plans a town hall on Friday, Feb. 10, to address “the widespread and uneven implications” of the U.S. executive order.

Back at Harvard, Saghazadeh worries the medical technology sector and universities in the U.S. will be scared to bring in Iranians and hire them. And she wonders about her years of education to get to Harvard.

“It’s a pity. I learned that if I work hard and play by the rules that I would get someplace. Now I feel like someone just broke the game,” she said.